Modernism: 1948 - 1967

In 1948, M. Belle Sweet retired and Lee Zimmerman took the helm as University Librarian. He would hold the position for nearly 20 years, a period neatly bifurcated by the library’s finally acquiring — for the first time in its history — its own building in 1957.

A Pennsylvannian, of Dutch ancestry, Zimmerman had graduated with a B.A. in history and political science from the University of Wisconsin in 1924; a B.S. from the University of Illinois in 1929; and an M.A. from the University of Illinois in 1932. He also completed graduate studies in librarianship at the University of Chicago, and worked at libraries in California and Minnesota (Virginia Junior College) before serving as Minnesota’s state librarian (1937-48).

Renowned for his dedication — and, at times, rigidity — Zimmerman was described by the Argonaut as:

first and foremost an administrator: unstinting, unbending, dedicated to the institution to which he was attached, a taskmaster always asking no more of others than of himself. He had a unique fund of energy with which to instrument his purposes. He seized on a problem and set to work at once to devise resolutions or controls… His favorite admonition was never to turn one’s back on a situation or difficulty.

One of the first major problems Zimmerman seized upon was the Idaho newspaper microfilming project, which occupied a large share of his attention for about 10 years, beginning in 1948. He served as chair of the Idaho Library Association’s microfilm committee from 1950 to ‘58 (and then as association president, 1959-60), which allowed him to put the weight of the association behind the project. The upshot was the preservation of invaluable local records (which were otherwise vulnerable to deterioration and fire) for study and research at multiple locations.

Among Zimmerman’s eccentricities was a love of cats that extended into the library itself. An officer of the American Feline Society, he and his wife kept several cats at home. The cats in the library belonged to a janitor, Fred Skog, a local character whom students were fond of (he earned the honorary title of “dean” and retired in 1952 as “head janitor, emeritus”). Skog kept the cats in the basement to catch mice, but Zimmerman had holes punched into the wall so they could enter the library when they wanted. Staff would arrive at work to find cats dozing on their desks. And at least one periodicals librarian became upset when the mousers defecated on the piles of newspapers. A cataloger, Stan Shepard, created a stir when he attempted to evict the cats from the library.

On the human front, Zimmerman sought to improve the wages and status of the librarians by promoting the library to the campus community and administration, through detailed biennial reports — and by creating a UI Library publication, The Bookmark. Featuring the writings of library staff, The Bookmark came to enjoy wide circulation both on-campus and across the country. As Zimmerman later recounted, "It was obviously necessary, as I saw it, to strive for faculty respect of library personnel through its understanding and contribution to the education process. [The Bookmark] and more sold us to faculty and administration…"

Some numbers may also bring information of general interest on the book collection itself, on the library’s functions, services and objectives; perhaps something also about our limitations on occasion.

The first Bookmark (September 1948) reported the resignation of second-in-command "Miss Agnes Peterson, Assistant Librarian and head of the Reference Department." After decades at the library — nearly her entire career — Peterson had departed within a few months of Sweet’s retirement and Zimmerman’s arrival.

Of the many house organs published by libraries for the information of their staffs and readers, none is more consistently interesting and valuable to the librarian beyond the local jurisdiction than the Bookmark… Librarian Lee Zimmerman and Humanities Librarian George Kellogg deserve high commendation for a difficult job well done.

Zimmerman also began visiting new libraries around the country in anticipation of a new standalone facility being built at the University of Idaho — he’d been told, at the time of his hiring, that one was in the works. And the need was obvious to the campus community, as expressed in a November 1946 Argonaut editorial:

The library service — to state it bluntly — is in a deplorable mess. Not that it is the fault of the librarian, the administration, or anyone connected with the operation… The fault lies with the university’s policy directors and planners… Although the Peabody report has commended the university for its selection of books, the present physical plant and its storage space has been rightly termed ‘impossible’. No student can do any serious research work without long hours of delay caused by waiting for important references to be brought from any one of a half-dozen storage places scattered over the Administration building.

During the late ’40s Zimmerman implemented some space-saving changes, including the replacement of nonadjustable wooden shelves with adjustable steel stacks. Microfilming also freed up space.

In 1951 the library became one of the few campus libraries to open up its stacks to undergraduate students — allowing them to browse the shelves and find books themselves. The same year, the library was repainted, redecorated and rearranged.

But by the mid ’50s the crowding was extreme. “The university’s library has been in temporary, makeshift and cramped quarters since 1909,” noted the Argonaut in 1954. The paper went on to print a passage from the 1954 accreditation report, under the headline, “Why Your University Needs: Library, Classroom Buildings”:

With book stacks jammed in so close together that you can scarcely pass through, and with collections located in unfinished basement rooms and corridors, with rather poor lighting, the staff, the faculty, and the students carry on cheerfully… It is recommended that that administration call to the attention of the people of Idaho the inadequacy of the present building…

But just as a new library building grew once again into a rallying cry, the planned site for the building — on the lawn north of the Administration Building — became a subject of heated debate. Detractors called it a “sacred” spot. University President J.E. Buchanan pointed out that the site had been approved by the Board of Regents in May 1947. “Where else would it go?” he told the Argonaut.

Eventually, in March 1955, the state legislature approved $1.3 million — about $550,000 short of the requested amount. And within weeks, the university chose a different site, just north of the Memorial Gymnasium. This site, not adjacent to the cherished Administration Building, meant a significant cost saving: the library could be designed as a relatively plain “box” — devoid of any gothic bric-a-brac necessary to blend with the admin building.

We believe the library is designed for efficient service and embodies the elements of simple beauty and functional unity.

Space was also trimmed to cut costs, wiping out areas intended for student services, audio-visual services and a museum. Cost per square foot was a thrifty $12. Making the best of the situation, Zimmerman noted, “The structure, architecturally, is done in contemporary style and is pleasantly simple. The length is 205 feet and the width, 138 feet. Area of the four floors totals 89,606 square feet… It will seat at one time a minimum of 1,090 readers and will have a book capacity of nearly 525,000 volumes."

Construction began May 9, 1956, and by January 1957 the structure was enclosed, 60% complete, and inside work began, the intention being to have it functioning and in-use by the start of classes that fall. But a steel workers strike delayed delivery of the book stacks, and by September the building was still an empty shell. It finally opened for use on October 23, and was dedicated on Saturday, November 2, “with a lot of pomp and circumstance, ribbon cutting, and a speech by Governor Robert E. Smylie,” recalled the then-new science librarian, Richard Beck.

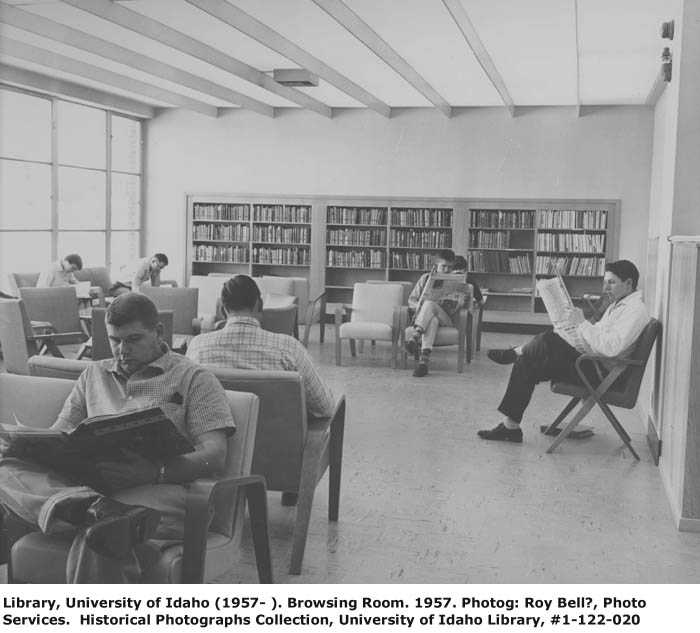

New-ish features included: unsupervised group-study rooms; soundproof rooms with typewriters; and a lounge or “browsing” room with newspapers and magazines. Zimmerman proudly published articles in Library Journal and other sources. “People in our profession are very interested in our library,” he told the Argonaut. “We think our building will have a great influence.”

Moving in the library’s 157,000 books and 530,000 documents required weeks — “one of the biggest wholesale operations in the [university’s] history,” noted the Daily Idahonian. A crew of 30 men worked two eight-hour shifts daily. Concurrently, many thousands of index and file cards had to be updated for the new location.

Staff in the news

March 1963 The Idahonian chronicles attempts by three librarians (Robert Burns, Paul Conditt and George Kellogg) to complete a “50-Mile Hike” (a craze at the time popularized by President John Kennedy, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and a national sense of “preparedness”). Footsore, they quit about halfway, at Genesee. “Book Hustlers Just Softies,” reports the Idahonian.

April 1963 Three of the four members of the university’s quiz bowl team, which competes in New York City on national TV, are library student assitants (George Alberts, Burton Hunter and Bill Siverly). Librarian Kellogg helps coach them.

By this time, the library’s full-time staff had grown to 11 professional librarians and seven clerical workers, and Zimmerman was pushing for three more of each. Forty students worked part-time. “Working so closely on the move brought about a heightened cohesiveness among the staff,” Beck recalled. “This spirit of devotion and enthusiasm continued” for years.

The new building inspired a wholesale reorganization of the library. In his 1956-57 biennial report to the president, Zimmerman noted: “In our old quarters functions were separated on the basis of form — reference collection, periodical collection, general collection, etc. In the new Library, they are integrated on the divisional concept… The arrangement of furniture, too, providing study islands within the stacks, has served to eliminate barriers between books and readers…” [This arrangement, however, would not survive. With its 1991 expansion, the library reverted mainly to the pre-1957 system.]

The 1950s and ’60s saw the library continue to build specialized and rare book collections, often through extraordinary donations. In 1950, Mrs. Lucy Day, widow of Jerome J. Day (who had previously donated his Pacific Northwest Americana collection in 1941), donated her late husband’s collection of rare books — some 1,365 volumes, many bound in leather and hand-tooled in gold by Italian craftsmen. Earl Larrison, a zoology professor, gave his collection of first editions of the works of Sir Walter Scott. And noted screenwriter Talbot Jennings, a UI graduate, donated several thousand books.

Meantime, the library acquired (and continues to acquire) all titles issued by Caxton Printers of Caldwell, Idaho, representing the publishing history of Idaho’s only nationally-known publisher. Zimmerman himself initiated a collection covering the history and culture of the Basque people — because of Idaho’s large Basque population, and because nothing comparable existed in the U.S.

Then in 1963, with help from Idaho Senator Frank Church, the library was designated a regional depository for U.S. Government publications — meaning it receives everything issued at no cost by the world’s largest publisher.

And in 1964 the library received more than 200,000 photographs taken of northern Idaho between 1894 and 1964 by the partnership of Nellie Stockbridge and T. N. Barnard. Along with the rare books, these nitrocellulose and glass-plate negatives, donated by Stockbridge’s heirs, are part of the library’s archival Special Collections division.

Library hours had more than doubled over the years — from 37.5 per week in 1893 to 76 by 1957. Nonetheless, during the late ’50s and early ’60s hours of operation became a heated subject of petitions, Argonaut editorials, an interim faculty committee, the ASUI executive and ultimately the president’s executive committee (similar to today’s Dean’s Council). More and more students wanted the library open as a place of study during hours that suited them personally, but the library’s budget was already stretched. As a compromise, hours were increased during exam times. (Today the library normally stays open more than 100 hours a week during the academic year, while a semi-external lounge — the "Fishbowl" — never closes.)

In January 1964 the modern era truly arrived when the library acquired its first dry-process photocopier — a leased Xerox 914 — for public and staff use (but kept behind the loans desk).

And photocopying skyrocketed. The previous year, staff had made about 1,000 copies on a small portable Contura copier which required freshly-stirred chemicals for each use. By contrast, during 1964, 61,000 copies were churned out on the new Xerox, with users paying a then-hefty 10 cents a copy. Indeed, the volume was high enough to justify continuing to lease the $30,000 Xerox. And there were other benefits, noted the March 1964 Bookmark: "Across the country, research libraries are restricting the loan of their journals and substituting photocopy instead. This saves time, wear and tear on library materials, and allows the borrower a permanent copy." Staff also hoped the copier would reduce theft and mutilation of books. And the following April, 1965, the library gained its first coin-operated copier (a Vicomatic) in the lobby.

In October 1964, the library began a massive project to re-classify its entire collection from the Dewey Decimal System (the favorite of public libraries) to Library of Congress (the system favored by the overwhelming majority of academic libraries). The project would occupy the next eight years.

And in June 1967, after 19 years at the helm, Zimmerman retired at the mandatory age of 65.